The Most Remote Place in the World

Illustrations by Anuj Shrestha

It’s called the “longest-swim problem”: If you had to drop someone at the place in the ocean farthest from any speck of land—the remotest spot on Earth—where would that place be? The answer, proposed only a few decades ago, is a location in the South Pacific with the coordinates 4852.5291ʹS 12323.5116ʹW: the “oceanic point of inaccessibility,” to use the formal name. It doesn’t get many visitors. But one morning last year, I met several people who had just come from there.

They had been sailing a 60-foot foiling boat, the Mālama, in the Ocean Race, a round-the-world yachting competition, and had passed near that very spot, halfway between New Zealand and South America. Now, two months later, they had paused briefly in Newport, Rhode Island, before tackling the final stretch across the Atlantic. (And the Mālama would win the race.) I spoke with some members of the five-person crew before going out with them for a sail on Narragansett Bay. When I asked about their experience at the oceanic pole of inaccessibility, they all brought up the weather.

With a test pilot’s understatement, the crew described the conditions as “significant” or “strong” or “noteworthy” (or, once, “incredibly noteworthy”). The Southern Ocean, which girds the planet in the latitudes above Antarctica and below the other continents, has the worst weather in the world because its waters circulate without any landmass to slow them down. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the most powerful on Earth, a conveyor belt that never stops and that in recent years has been moving faster. These are the waters that tossed Roald Amundsen and Ernest Shackleton. The winds are cold and brutal. Waves reach 60 or 70 feet. In a second, a racing boat’s speed can drop from 30 knots to five, then jump back to 30. You may have to ride out these conditions, slammed and jammed, for five days, 10 days, trimming sails from inside a tiny sealed cockpit, unable to stand up fully all that time. To sleep, you strap yourself into a harness. You may wake up bruised.

[Read: The last place on Earth any tourist should go]

This is not a forgiving environment for a sailboat. But it’s a natural habitat for the albatross you find yourself watching through a foggy pane as it floats on air blowing across the water’s surface—gliding tightly down one enormous wave and then tightly up the next. The bird has a 10-foot wingspan, but the wings do not pump; locked and motionless, they achieve aerodynamic perfection. The albatross gives no thought to the longest swim. It may not have touched land in years.

The oceanic pole of inaccessibility goes by a more colloquial name: Point Nemo. The reference is not to the Disney fish, but to the captain in Jules Verne’s novel Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. In Latin, nemo means “no one,” which is appropriate because there is nothing and no one here. Point Nemo lies beyond any national jurisdiction. According to Flightradar24, a tracking site, the occasional commercial flight from Sydney or Auckland to Santiago flies overhead, when the wind is right. But no shipping lanes pass through Point Nemo. No country maintains a naval presence. Owing to eccentricities of the South Pacific Gyre, the sea here lacks nutrients to sustain much in the way of life—it is a marine desert. Because biological activity is minimal, the water is the clearest of any ocean.

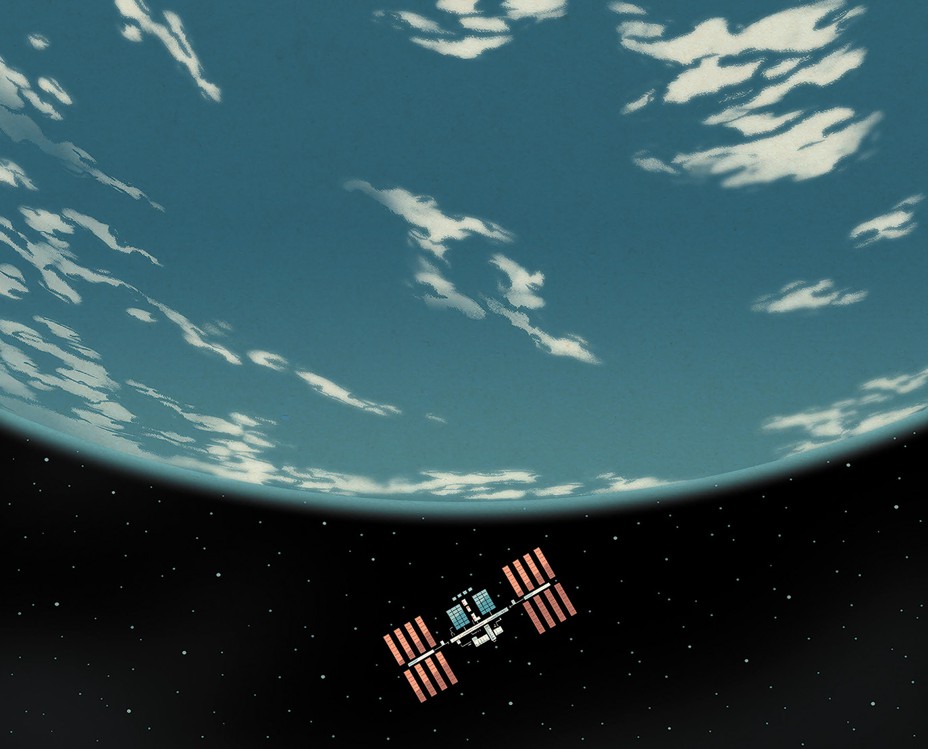

What you do find in the broad swath of ocean around Point Nemo—at the bottom of the sea, two and a half miles below the surface—are the remains of spacecraft. They were brought down deliberately by means of a controlled deorbit, the idea being that the oceanic point of inaccessibility makes a better landing zone than someone’s rooftop in Florida or North Carolina. Parts of the old Soviet Mir space station are here somewhere, as are bits and pieces of more than 250 other spacecraft and their payloads. They had been sent beyond the planet’s atmosphere by half a dozen space agencies and a few private companies, and then their lives came to an end. There is a symmetry in the outer-space connection: If you are on a boat at Point Nemo, the closest human beings will likely be the astronauts aboard the International Space Station; it periodically passes directly above, at an altitude of about 250 miles. When their paths crossed at Point Nemo, the ISS astronauts and the sailors aboard the Mālama exchanged messages.

Illustration by Anuj Shrestha

Illustration by Anuj Shrestha

The Mālama’s crew spoke with me about the experience of remoteness. At Point Nemo, they noted, there is no place to escape to. If a mast breaks, the closest help, by ship, from Chile or New Zealand, could be a week or two away. You need to be able to fix anything—sails, engines, electronics, the hull itself. The crew described sensations of rare clarity and acuity brought on by the sheer scale of risk. The austral environment adds a stark visual dimension. At this far-southern latitude, the interplay of light and cloud can be intense: the darks so very dark, the brights so very bright.

Simon Fisher, the Mālama’s navigator, described feeling like a trespasser as the boat approached Point Nemo—intruding where human beings do not belong. Crew members also described feelings of privilege and power. “There’s something very special,” Fisher said, “about knowing you’re someplace where everybody else isn’t.”

We all know the feeling. Rain-swept moors, trackless deserts, unpeopled islands. For me, such places are hard to resist. Metaphorically, of course, remoteness can be found anywhere—cities, books, relationships. But physical remoteness is a category of its own. It is an enhancer: It can make the glorious better and the terrible worse. The oceanic pole of inaccessibility distills physical remoteness on our planet into a pure and absolute form. There are continental poles of inaccessibility too—the place on each landmass that is farthest from the sea. But these locations are not always so remote. You can drive to some of them. People may live nearby. (The North American pole of inaccessibility is on the Pine Ridge Reservation, in South Dakota.) But Point Nemo is nearly impossible to get to and offers nothing when you arrive, not even a place to stand. It is the anti-Everest: It beckons because nothing is there.

I first heard the name Point Nemo in 1997, when hydrophones on the floor of the South Pacific, thousands of miles apart, picked up the loudest underwater sound ever recorded. This got headlines, and the sound was quickly named the “Bloop.” What could be its source? Some speculated about an undiscovered form of marine life lurking in the abyssal depths. There was dark talk about Russian or American military activity. Readers of H. P. Lovecraft remembered that his undersea zombie city of R’lyeh was supposedly not far away. Scientists at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration eventually concluded that the sound had come from the fracturing or calving of ice in Antarctica. In this instance, freakish conditions had directed the sound of an Antarctic event northward, toward a lonely expanse of ocean. Faraway hydrophones then picked up the sound and mistook its place of origin. News reports noted the proximity to Point Nemo.

[Video: The loudest underwater sound ever recorded has no scientific explanation]

You might have thought that a planetary feature as singular as the oceanic pole of inaccessibility would be as familiar as the North Pole or the equator. In a sci-fi story, this spot in the South Pacific might be a portal to some other dimension—or possibly the nexus of the universe, as the intersection of First and First in Manhattan was once said to be. Yet at the time of the Bloop, the location of the oceanic pole of inaccessibility had been known and named for only five years.

I have not been to Point Nemo, though it has maintained a curious hold on me for decades. Not long ago, I set out to find the handful of people on Earth who have some sort of personal connection to the place. I started with the man who put it on the map.

Hrvoje Lukatela, a Croatian-born engineer, left his homeland in the 1970s as political and intellectual life there became turbulent. At the University of Zagreb, he had studied geodesy—the science of measuring Earth’s physical properties, such as its shape and its orientation in space. Degree in hand, he eventually found his way to Calgary, Alberta, where he still lives and where I spent a few days with him last fall. At 81, he is no longer the avid mountaineer he once was, but he remains fit and bluff and gregarious. A trim gray beard and unkempt hair add a slight Ewok cast to his features.

After arriving in Canada, Lukatela was employed as a survey engineer. For several years, he worked on the Alaska Highway natural-gas pipeline. For another company, he determined the qibla—the precise alignment toward the Kaaba, in Mecca—for a new university and its mosque in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. In time, he created a software company whose product he named after the Greek astronomer Hipparchus. This was in the 1980s, when digital cartography was advancing rapidly and civilian GPS systems were on the horizon. The Hipparchus software library—“a family of algorithms that dealt with differential geometry on the surface of an ellipsoid,” as he described it, intending to be helpful—made it easier to bridge, mathematically, three-dimensional and two-dimensional geographical measurements. Lukatela can go on at length about the capabilities of Hipparchus, which he eventually sold to Microsoft, but two of the most significant were its power and its accuracy.

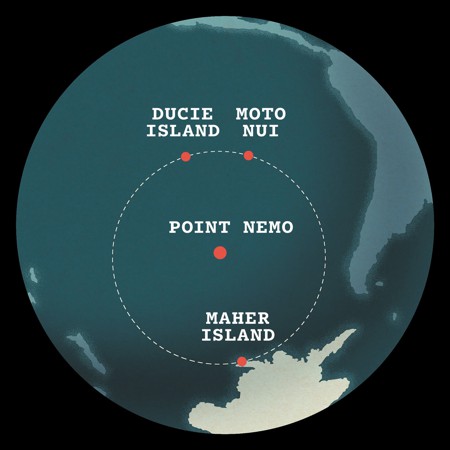

By his own admission, Lukatela is the kind of man who will not ask for directions. But he has a taste for geographical puzzles. He heard about the longest-swim problem from a friend at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution and was immediately engaged. You could twirl a classroom globe and guess, correctly, that the oceanic pole of inaccessibility must lie in the South Pacific, probably concealed by the rectangle where most publishers of maps and globes put their logo. But no one had tried to establish the exact location. As Lukatela saw it, the logic of the search process was simple. It takes three points to define a circle. Lukatela needed to find the largest oceanic circle that met two criteria: The circumference had to be defined by three points of dry land. And inside the circle there could be no land at all. The oceanic point of inaccessibility would be the center of that circle.

I’ll leave the computational churning aside, except to say that Hipparchus was made for a problem like this. Drawing on a digitized cartographic database, it could generate millions of random locations in the ocean and calculate the distance from each on a spherical surface to the nearest point of land. Lukatela eventually found the three “proximity vertices” he needed. One of them is Ducie Island, a tiny atoll notable for a shark-infested lagoon. It is part of the Pitcairn Islands, a British overseas territory, where in 1790 the Bounty mutineers made their unhappy home. A second vertex is the even tinier Motu Nui, a Chilean possession, whose crags rise to the west of Easter Island. The character Moana, in the animated movie, comes from there. The third vertex is desolate Maher Island, off the coast of Antarctica. It is a breeding ground for Adélie penguins. The three islands define a circle of ocean larger than the old Soviet Union. Point Nemo, at the center, lies 1,670.4 miles from each vertex. For perspective, that is roughly the distance from Manhattan to Santa Fe.

Lukatela completed his calculations in 1992, and quietly shared the results with his friend at Woods Hole and a few other colleagues. As the young internet gained users, word about Point Nemo spread among a small subculture of geodesists, techies, and the simply curious. In time, new cartographic databases became available, moving the triangulation points slightly. Lukatela tried out two of the databases, each recalibration giving Point Nemo itself a nudge, but not by much.

Lukatela had named the oceanic pole of inaccessibility after the mysterious captain in the Jules Verne novel he had loved as a boy. Submerged in his steampunk submarine, Captain Nemo sought to keep his distance from terrestrial woes: “Here alone do I find independence! Here I recognize no superiors! Here I’m free!”

But Captain Nemo couldn’t entirely stay aloof from the rest of the planet, and neither can Point Nemo. Many of the boats in the Ocean Race carry a “science package”— equipment for collecting weather data and water samples from regions of the sea that are otherwise nearly impossible to monitor. Data collected by their instruments, later given to labs, reveal the presence of microplastics: Even at the oceanic point of inaccessibility, you are not beyond the reach of humanity.

An article this past spring in the journal Nature reported the results of a scientific expedition that bored deep into the sediment of the ocean floor near Point Nemo. The focus was on the fluctuating character, over millions of years, of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, whose existence became possible after tectonic forces separated Australia and South America from Antarctica. The current helps regulate temperatures worldwide and keep Antarctica cold. But, as the Nature article explained, its character is changing.

I spent several hours recently with one of the article’s authors, Gisela Winckler, at Columbia University’s Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, high on the Palisades overlooking the Hudson River. Winckler is a physicist and an oceanographer, and her interest in oceans and paleoclimate goes back to her graduate-school days at Heidelberg University, in Germany. She confessed that she’d first learned about Point Nemo not from a scientific paper but from the 2010 album Plastic Beach, by Damon Albarn’s project Gorillaz. Winckler is intrepid; early in her career, a quarter century ago, she descended to the Pacific floor in the submersible Alvin, looking for gas hydrates and methane seeps. Yellow foul-weather gear hangs behind her office door. On a table sits a drill bit used for collecting sediment samples. Water from Point Nemo is preserved in a vial.

Illustration by Anuj Shrestha

Illustration by Anuj Shrestha

Winckler’s two-month expedition aboard the drilling vessel JOIDES Resolution, in 2019, was arduous. Scientists and crew members set out from Punta Arenas, Chile, near the start of the dark austral winter; they would not encounter another ship. The seas turned angry as soon as the Resolution left the Strait of Magellan, and stayed that way. The shipboard doctor got to know everyone. Winckler shrugged at the memory. That’s the Southern Ocean for you. The drill sites had been chosen because the South Pacific is understudied and because the area around Point Nemo had sediment of the right character: so thick and dense with datable microfossils that you can go back a million years and sometimes be able to tell what was happening century by century. The team went back further in time than that. The drills punched through the Pleistocene and into the Pliocene, collecting core samples down to a depth corresponding to 5 million years ago and beyond.

The work was frequently interrupted by WOW alerts—the acronym stands for “waiting on weather”—when the heave of the ship made drilling too dangerous. Five weeks into the expedition, a violent weather system the size of Australia came roaring from the west. The alert status hit the highest level—RAW, for “run away from weather”—and the Resolution ran.

But the team had collected enough. It would spend the next five years comparing sediment data with what is known or surmised about global temperatures through the ages. A 5-million-year pattern began to emerge. As Winckler explained, “During colder times, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current itself becomes cooler and slows down, shifting a little bit northward, toward the equator. But during warmer times, it warms and speeds up, shifting its latitude a little bit southward, toward the pole.” The current is warming now and therefore speeding up, and its course is more southerly—all of which erodes the Antarctic ice sheet. Warm water does more damage to ice than warm air can do.

Before I left the Palisades, Winckler walked me over to the Lamont-Doherty Core Repository, a sediment library where more than 20,000 tubes from decades of expeditions are stacked on floor-to-ceiling racks. The library was very cold—it’s kept at 2 degrees centigrade, the temperature of the sea bottom—and very humid. Open a tube, and the sediment may still be moist. I wondered idly if in her Point Nemo investigations Winckler had ever run into a bit of space junk. She laughed. No, the expedition hadn’t deployed underwater video, and the chances would have been infinitesimal anyway. Then again, she said, you never know. Some 30 years ago, during an expedition in the North Atlantic, she had seen a bottle of Beck’s beer from an array of cameras being towed a mile or two below the surface. In 2022, in the South Pacific, the headlights of a submersible at the bottom of the Mariana Trench—about seven miles down, the deepest spot in any ocean—picked up the glassy green of another beer bottle resting in the sediment.

Jonathan McDowell has never been to the ocean floor, but he does have a rough idea where the world’s oceanic space junk can be found. McDowell is an astronomer and astrophysicist at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, in Cambridge, Massachusetts. He is also part of the team that manages science operations for the Chandra deep-space X-ray telescope. At more or less monthly intervals, he publishes a newsletter, Jonathan’s Space Report, notable for its wide-ranging expertise and quirky humor. He has written about Point Nemo and its environs, and in an annual report, he provides long lists, in teletype font, with the coordinates of known debris splashdowns.

British by parentage and upbringing, McDowell looks ready to step into the role of Doctor Who: rumpled dark suit, colorful T-shirt, hair like a yogi’s. He is 64, which he mentioned was 34 if you count in Martian years. I met him at his lair, in a gritty district near Cambridge—some 1,900 square feet of loft space crammed with books and computers, maps and globes. One shelf displays a plush-toy Tribble from a famous Star Trek episode. A small container on another shelf holds a washer from the camera of a U.S. spy satellite launched into orbit in 1962.

McDowell has been preoccupied by spaceflight all his life. His father was a physicist who taught at Royal Holloway, University of London. As a teenager, he began keeping track of rocket launches. In maturity, McDowell has realized a grander ambition: documenting the history of every object that has left the planet for outer space. Nothing is beneath his notice. He has studied orbiting bins of garbage discarded decades ago by Russia’s Salyut space stations. If a Beck’s bottle were circling the planet, he’d probably know. McDowell estimates that the thousands of files in binder boxes on his shelves hold physical records of 99 percent of all the objects that have made it into orbit. For what it covers, no database in the world matches the one in McDowell’s loft.

Unless something is in very high orbit, what goes up eventually comes down, by means of a controlled or uncontrolled deorbit. The pieces of rockets and satellites and space stations large enough to survive atmospheric reentry have to hit the planet’s surface somewhere. McDowell pulled several pages from a printer—colored maps with tiny dots showing places around the world where space debris has fallen. The maps reveal a cluster of dots spanning the South Pacific, like a mirror held up to the Milky Way.

Guiding objects carefully back to Earth became a priority after 1979, when the reentry of the American space station Skylab went awry and large chunks of debris rained down on southern Australia. No one was hurt, McDowell said, but NASA became an object of ridicule. The coastal town of Esperance made international news when it tried to fine the space agency for littering. From the 1990s on, more and more satellites were launched into orbit; the rockets that put them there were designed to fall back to Earth. The empty ocean around Point Nemo became a primary target zone: a “spacecraft cemetery,” as it’s sometimes called. That’s where Mir came down, in 2001. It’s where most of the spacecraft that supply the International Space Station come down. There are other cemeteries in other oceans, but the South Pacific is Forest Lawn. The reentry process is not an exact science, so the potential paths, while narrow, may be 1,000 miles long. When reentry is imminent, warnings go out to keep ships away.

Illustration by Anuj Shrestha

Illustration by Anuj Shrestha

When I mentioned the conversation between the Mālama crew and its nearest neighbors, the space-station astronauts, McDowell pointed me toward a bank of flatscreens. He called up a three-dimensional image of Earth and then showed me the orbital path of the ISS over the previous 24 hours. Relative to the universe, he explained, the plane of the ISS orbit never changes—the station goes round and round, 16 times a day, five miles a second. But because the globe is spinning underneath, each orbit covers a different slice of the world—now China, now India, now Arabia. McDowell retrieved a moment from the day before. The red line of the orbit unspooled from between Antarctica and New Zealand and traced a path northeast across the Pacific. He pointed to the time stamp and the location. At least once a day, he said, the space station will be above Point Nemo.

[Read: A close look at the most distant object NASA has ever explored]

McDowell is drawn to the idea of remoteness, which maybe shouldn’t be surprising: To an astrophysicist, remoteness is never far away. But, he said, “there are layers and layers when it comes to how you think about it.” In 2019, a space probe relayed pictures of a 22-mile-long rock known as Arrokoth, the most distant object in our solar system ever to be visited by a spacecraft. That’s one kind of remote. More recently, the James Webb Space Telescope has found galaxies more distant from our own than any known before. That’s another kind. McDowell brought the subject almost back to Earth. On our planet, he said, Point Nemo is definitely remote—as remote as you can get. “But I’m always moved by the thought of Mike Collins, who was the first person to be completely isolated from the rest of humanity when his two friends were on the moon and he was orbiting the far side, and he had the moon between him and every other human being who has ever lived.”

Collins himself wrote of that moment: “I am alone now, truly alone, and absolutely isolated from any known life. I am it.”

I joined Hrvoje Lukatela and his wife, Dunja, for dinner one evening at their home near the University of Calgary. Hrvoje and Dunja had met at university as young mountaineers—outdoors clubs offered a form of insulation from the Communist regime. They emigrated together soon after their marriage. In the basement office of their home, he still keeps his boyhood copy (in Croatian) of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Lukatela spread maps and computer printouts on the table as we ate.

Lukatela might wish to be remembered for the Hipparchus software library, but he accepts that the first line of his obituary will probably be about Point Nemo. He is proud of his discovery, and like a man with a hammer, he has a tendency to see everything as a nail. He and Dunja spend part of the year in Croatia, and in an email this past spring, he sent me some new calculations that solve the longest-swim problem for the Adriatic Sea (“with millimetric numerical precision”). Set him down alongside Loch Ness or the Central Park Reservoir, and I can guess what he’d be thinking.

Lukatela has a dream for Point Nemo, though probably not one that he can pursue alone. His hope is that someone, someday, will venture into the South Pacific and leave GPS receivers on Ducie Island, Motu Nui Island, and Maher Island, establishing the location of the triangulation points more accurately than ever before. While they’re at it, they might also drive brass geodetic markers into the rock. Ducie and Motu Nui would be relatively easy to get to—“I could do it on my own,” he ventured. (Dunja, listening, did not seem overly concerned.) Access to Maher Island, Lukatela went on, with its inhospitable location and brutal weather, might require some sort of government expedition.

[From the February 1906 issue: A history and future of human exploration]

What government would that even be? Lukatela indicated Maher Island on a map. Officially, it is part of Marie Byrd Land, one of the planet’s few remaining tracts of terra nullius—land claimed by no one. But Lukatela recalled hearing that Maher Island had recently come under the jurisdiction of one of those start-up micronations that people invent to advance some cause.

He was right. Maher is one of five Antarctic islands claimed by the Grand Duchy of Flandrensis, a Belgium-based micronation devoted to raising ecological awareness. At international conferences, the grand duke, Nicholas de Mersch d’Oyenberghe, wears military dress blues with handsome decorations and a yellow sash. But he answers his own email. Asked about Lukatela’s ambition, he explained that his country is the only one in the world that seeks to bar all human beings from its territory; the thousand or so people who have registered as citizens are all nonresidents. “No humans, only nature!” is the Grand Duchy’s motto. However, he went on, a mission to install a GPS receiver and a geodetic-survey marker would be deemed scientific, and welcomed. The Grand Duchy would be happy to provide a flag.

The astronaut Steve Bowen has orbited above Maher Island and Point Nemo many times. Before being selected by NASA, Bowen was a submariner; he knows a lot about life in a sealed container far from anywhere. He was one of the crew members aboard the International Space Station who spoke with the Ocean Race sailors as their trajectories crossed at Point Nemo. When I caught up with him this past summer, he compared his circumstances and theirs. The astronauts sleep a lot better, he said—in microgravity, you don’t wake up bruised. But the environment never changes. There is no fresh air, no wind, no rain. Bowen remembered the exhilaration whenever his submarine surfaced in open sea and he would emerge topside into the briny spray, tethered to the boat, taking in a view of nothing but water in every direction.

In the space station, Bowen would often float his way to the seven-window cupola—the observation module—and gaze at the planet below. From that altitude, you have a sight line extending 1,000 miles in every direction, an area about the size of Brazil. In a swath of the planet that big, Bowen said, you can almost always find a reference point—an island, a peninsula, something. The one exception: when the orbit takes you above Point Nemo. For a while, the view through the windows is all ocean.

That same expanse of ocean will one day receive the International Space Station. When it is decommissioned, in 2031, the parts that don’t burn up in the atmosphere will descend toward the South Pacific and its spacecraft cemetery.

Last March, aboard a chartered ship called the Hanse Explorer, a Yorkshire businessman named Chris Brown, 62, exchanged messages with Lukatela to make sure that he had the coordinates he needed—the original computation and the later variations. Brown values precision. As he explained when I reached him at his home in Harrogate after his return from the South Pacific, he and his son Mika had been determined to reach Point Nemo, and even have a swim, and he wanted to be certain he was in the right neighborhood.

This wasn’t just a lark. Brown has been attempting to visit all eight of the planet’s poles of inaccessibility, and he had already knocked off most of the continental ones. Point Nemo, the oceanic pole, was by far the most difficult. Brown is an adventurer, but he is also pragmatic. He once made arrangements to descend to the Titanic aboard the Titan submersible but withdrew in short order because of safety concerns—well founded, as it turned out, given the Titan’s tragic implosion in 2023. The ship he was chartering now could stay at sea for 40 days and was built for ice. Autumn had just begun in the Southern Hemisphere when the Browns left Puerto Montt, Chile, and the weather turned unfriendly at once. “Nausea was never far away,” he recalled.

[Read: The Titanic sub and the draw of extreme tourism]

But approaching Point Nemo, eight days later, the Hanse Explorer found a brief window of calm. Steering a Zodiac inflatable boat and guided by a GPS device, Brown made his way to 4852.5291ʹS 12323.5116ʹW. He and Mika slipped overboard in their wetsuits, becoming the first human beings to enter the ocean here. A video of the event includes photos of the men being ferociously attacked by an albatross. While treading water, they managed to display the maritime flags for the letters N, E, M, and O. Then, mindful of Lukatela’s further calculations, they headed for two other spots, a few miles distant—just to be safe. Admiral Robert Peary’s claim to have been the first person to reach the North Pole, in 1909, has long been disputed; his math was almost certainly off. Brown did not want to become the Peary of Point Nemo.

He isn’t, of course. I think of him, rather, as Point Nemo’s Leif Erikson, the man credited with the first New World toe-touch by a European. I think of Hrvoje Lukatela as some combination of Juan de la Cosa and Martin Waldseemüller, the cartographers who first mapped and named the Western Hemisphere. Jonathan McDowell is perhaps Point Nemo’s Alexander von Humboldt, Gisela Winckler its Charles Lyell and Gertrude Bell. Steve Bowen and the Ocean Race crew, circumnavigating the globe in their different ways, have a wide choice of forebears. The grand duke of Flandrensis may not be Metternich, but he introduces a hint of geopolitics.

Unpopulated and in the middle of nowhere, Point Nemo is starting to have a history.

This article appears in the November 2024 print edition with the headline “The Most Remote Place in the World.” When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.