Millennials Are Now Pining for Their Youth. Welcome.

This is an edition of the Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

Be warned: I am a (late–) Gen X man attempting to write about the culture of Millennials, mostly women. I’m well aware of the dichotomies pitting “us” against “them”—my generation is complacent, sarcastic, and lucky; theirs is stocked with phone-addicted, perma-renter sellouts. In my darkest moments, I’m even prone to believe the stereotypes. But two recent Atlantic articles, both about Millennials approaching middle age, convinced me that more connects the groups than divides them.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

The problem with moral purity The bold compassion of Dear Dickhead Let us now praise undecided voters Five books that conjure entirely new worldsBecause both articles—Amy Weiss-Meyer’s analysis of Sally Rooney’s new novel, Intermezzo, and Hannah Giorgis’s dissection of the Hulu series How to Die Alone—home in on what separates Millennials from other age cohorts, I’ll admit mine is a weird reaction. Giorgis contrasts writer-actor Natasha Rothwell’s new comedy, about a 35-year-old airport worker who has “no savings, no real friends, and no romantic prospects,” with shows such as Girls, Insecure, Atlanta, and Broad City. “Unlike those comedies about feckless 20-somethings, which premiered in the 2010s, How to Die Alone focuses on the arrested adolescence of a Millennial who’s now in her mid-30s, and still not doing much better,” Giorgis writes. She traces the angst suffered by Mel, Rothwell’s protagonist, to the travails of her post-recession generation, wrestling “with what it means to even try when opportunities for career advancement come few and far between.”

Weiss-Meyer frames the fourth novel by Rooney, who at 33 is already considered “a generational portraitist,” as a work “preoccupied with questions of age and age difference; questions cosmetic, practical, ethical, and existential.” Intermezzo, whose characters are mostly in their early 20s or early 30s, fixates on age gaps within relationships both romantic and familial. It is also, unavoidably, a book about a generation aging out of the moment when its youthful yearnings, consumer preferences, and rebellious rage dominated the cultural conversation. In short, there’s a new gang in town. “Gen Z has officially entered the Rooneyverse,” Weiss-Meyer writes, “and they’re making the Millennials feel old.”

This is something a Gen Xer can certainly relate to. We, too, were in the media spotlight before Millennials, Snapchat, and avocado toast pulled focus from us. More important, we also once reached a point at which mortality began to feel real. As Weiss-Meyer writes, “Rooney’s latest characters, newly alert to the weight of years, are as attuned to regret as to anticipation; they’re preoccupied with what kind of person they have already been. Looking more warily in the mirror, they don’t always like what they see.”

That is a beautiful distillation of aging, and it isn’t specific to Millennials, nor are the forces plaguing that generation—financial pressures, ethical dilemmas, the corporate capture of the American dream. Gen X didn’t endure two traumatic recessions, school lockdowns, and a forever war, but we did have nuclear-bomb drills; we were also the subject of hand-wringing over possibly becoming the first American generation to be worse off than our parents.

I agree with Giorgis that Girls, Insecure, and Broad City illuminated the struggles of Millennial youth. But I loved watching those shows because they captured the experience of being in one’s 20s in a major city—regardless of generation. They all shared DNA with Gen X touchstone films such as Singles and Reality Bites. In the same way, Intermezzo and How to Die Alone are universally about getting not-so-young, about weariness seeping in through the margins, about the transition from railing against the impossible expectations of others to realizing you had some unattainable dreams of your own.

The point isn’t to say that Gen X and Millennials have the same struggles. It’s merely that every generation is relatively poor and happy in youth, fretful in middle age, and then … well, I don’t quite know yet, but I’ve read that it gets better. The boundaries of age groups are porous, and these groups are learning from and influencing one another. We speak, read, watch, and work across generations, and as long as we do, our troubles are not ours alone.

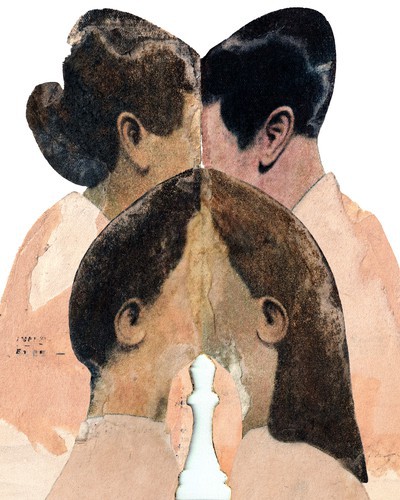

Illustration by Aldo Jarillo

Illustration by Aldo Jarillo

The Rooneyverse Comes of Age

By Amy Weiss-Meyer

In her new novel, Intermezzo, Sally Rooney moves past the travails of youth into the torments of mortality.

What to Read

Connected, by Nicholas A. Christakis and James H. Fowler

To truly understand people, don’t focus on individuals or groups, the social scientists Christakis and Fowler write. What matter are the connections between people: the branching paths that extend from you and your family, friends, colleagues, and neighbors to, say, Kevin Bacon. The book sketches out the surprising ways that these social networks sway our behavior, moods, and health, and its conclusions can be mind-bending. If your best friend’s sister gains weight, for example, you’re more likely to gain weight too, they write. Who we know significantly affects whether we smoke, die by suicide, or vote, thanks to our human tendency to copy one another. Happiness and sadness also spread among groups, so that the mood of a person you don’t know can sway your own emotions—even though we often imagine that our internal states are under our personal control. “No man or woman is an island,” the authors write. Their book makes a convincing case that our tangled relationships determine nearly everything about how our life plays out—and reminds us that we can’t be meaningfully understood in isolation. — Chelsea Leu

From our list: Seven books that demystify human behavior

Out Next Week