The Lynching of Bob Broome

Photographs by Olivia Joan Galli

Last fall, on an overcast Sunday morning, I took a train from New York to Montclair, New Jersey, to see Auntie, my mother’s older sister. Auntie is our family archivist, the woman we turn to when we want to understand where we came from. She’s taken to genealogy, tending our family tree, keeping up with distant cousins I’ve never met. But she has also spent the past decade unearthing a different sort of history, a kind that many Black families like mine leave buried, or never discover at all. It was this history I’d come to talk with her about.

Auntie picked me up at the train station and drove me to her house. When she unlocked the door, I felt like I was walking into my childhood. Everything in her home seemed exactly as it had been when I spent Christmases there with my grandmother—the burgundy carpets; the piano that Auntie plays masterfully; the dining-room table where we all used to sit, talk, and eat. That day, Auntie had prepared us a lunch to share: tender pieces of beef, sweet potatoes, kale, and the baked rice my grandma Victoria used to make.

When Auntie went to the kitchen to gather the food, I scanned the table. At the center was a map of Mississippi, unfurled, the top weighted down with an apple-shaped trivet. Auntie told me that the map had belonged to Victoria. She had kept it in her bedroom, mounted above the wood paneling that lined her room in Princeton, New Jersey, where she and my grandfather raised my mother, Auntie, and my two uncles. I’d never noticed my grandmother’s map, but a framed outline of Mississippi now hangs from a wall in my own bedroom, the major cities marked with blooming magnolias, the state flower. My grandmother had left markings on her map—X’s over Meridian, Vicksburg, and Jackson, and a shaded dot over a town in Hinds County, between Jackson and Vicksburg, called Edwards.

I wondered whether the X’s indicated havens or sites of tragedy. As for Edwards, I knew the dot represented the start of Auntie’s story. Following an act of brutality in 1888, my ancestors began the process of uprooting themselves from the town, ushering themselves into a defining era of Black life in America: the Great Migration.

I first learned about the lynching of Bob Broome in 2015, when Auntie emailed my mother a PDF of news clippings describing the events leading up to his murder. She’d come across the clippings on Ancestry.com, on the profile page of a distant family member. Bob was Victoria’s great-uncle. “Another piece of family history from Mississippi we never knew about,” Auntie wrote. “I’M SURE there is more to this story.”

I knew that her discovery was important, but I didn’t feel capable then of trying to make sense of what it meant to me. As I embarked on a career telling other people’s stories, however, I eventually realized that the lynching was a hole in my own, something I needed to investigate if I was to understand who I am and where I came from. A few years ago, I began reading every newspaper account of Bob Broome’s life and death that Auntie and I could find. I learned more about him and about the aftermath of his killing. But in the maddeningly threadbare historical record, I also found accounts and sources that contradicted one another.

Bob Broome was 19 or 20 when he was killed. On August 12, 1888, a Sunday, he walked to church with a group of several “colored girls,” according to multiple accounts, as he probably did every week. All versions of the story agree that on this walk, Bob and his company came across a white man escorting a woman to church. Back then in Mississippi, the proper thing for a Black man to do in that situation would have been to yield the sidewalk and walk in the street. But my uncle decided not to.

A report out of nearby Jackson alleges that Bob pushed the white man, E. B. Robertson, who responded with a promise that Bob “would see him again.” According to the Sacramento Daily Union (the story was syndicated across the country), my uncle’s group pushed the woman in a rude manner and told Robertson they would “get him.” After church, Robertson was with three or four friends, explaining the sidewalk interaction, when “six negroes” rushed them.

All of these stories appeared in the white press. According to these accounts, Bob and his companions, including his brother Ike, my great-great-grandfather, approached Robertson’s group outside a store. The papers say my uncle Bob and a man named Curtis Shortney opened fire. One of the white men, Dr. L. W. Holliday, was shot in the head and ultimately died; two other white men were injured. Several newspaper stories claim my uncle shot Holliday, with a couple calling him the “ring leader.” It is unclear exactly whom reporters interviewed for these articles, but if the reporting went as it usually did for lynchings, these were white journalists talking to white sources. Every article claims that the white men were either unarmed or had weapons but never fired them.

Bob, his brother Ike, and a third Black man were arrested that day; their companions, including Shortney, fled the scene. While Bob was being held in a jail in nearby Utica, a mob of hundreds of white men entered and abducted him. Bob, “before being hanged, vehemently protested his innocence,” The New York Times reported. But just a few beats later, the Times all but calls my uncle a liar, insisting that his proclamation was “known to be a contradiction on its face.” Members of the mob threw a rope over an oak-tree branch at the local cemetery and hauled my ancestor upward, hanging him until he choked to death. A lynch mob killed Shortney a month later.

[From the May 2022 issue: Burying a burning]

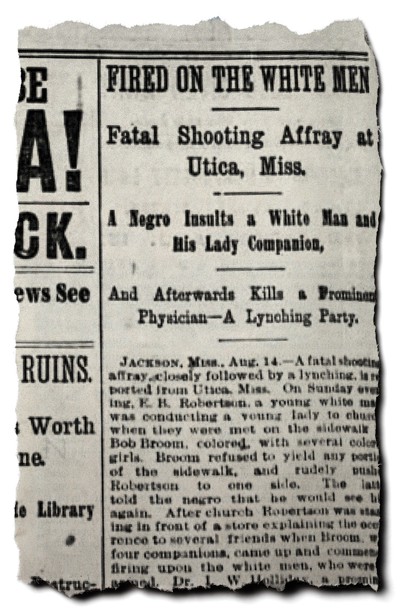

In the white press, these lynchings are described as ordinary facts of life, the stories sandwiched between reports about Treasury bonds and an upcoming eclipse. The Times article about Bob noted that days after his lynching, all was quiet again in Utica, “as if nothing had occurred.” The headlines from across the country focus on the allegations against my uncle, treating his extralegal murder simply as a matter of course. The Boston Globe’s headline read “Fired on the White Men” and, a few lines later, “A Negro Insults a White Man and His Lady Companion.” The subtitle of The Daily Commercial Herald, a white newspaper in nearby Vicksburg, Mississippi, read: “Murderous and Insolent Negro Hanged by Indignant Citizens of Utica.”

The summary executions of Bob Broome and Curtis Shortney had the convenient effect of leaving these stories in white-owned newspapers largely unexamined and unchallenged in the public record. But the Black press was incredulous. In the pages of The Richmond Planet, a Black newspaper in Virginia’s capital, Auntie had found a column dismissing the widespread characterization of Bob as a menace. This report was skeptical of the white newspapers’ coverage, arguing that it was more likely that the white men had attacked the Black group, who shot back. “Of course it is claimed that the attack was sudden and no resistance was made by the whites,” the article reads.

The author and her aunt at her aunt’s home in New Jersey (Olivia Joan Galli for The Atlantic)

The author and her aunt at her aunt’s home in New Jersey (Olivia Joan Galli for The Atlantic)

The newspapers we found don’t say much more about the lynching, but Auntie did find one additional account of Bob Broome’s final moments—and about what happened to my great-great-grandfather Ike. A few days after the lynching, a reader wrote to the editor of The Daily Commercial Herald claiming to have been a witness to key events. “Knowing you always want to give your readers the correct views on all subjects,” the letter opens, the witness offers to provide more of “the particulars” of my uncle’s lynching. According to the letter writer, when the lynch mob arrived the morning after the shooting, the white deputy sheriff, John Broome, assisted by two white men, E. H. Broome and D. T. Yates, told the crowd that they could not take the prisoners away until the case was investigated. Bob, Ike, and the third Black man were moved to the mayor’s office in the meantime. But more men from neighboring counties joined the mob and showed up at the mayor’s office, where they “badly hurt” Deputy Sheriff Broome with the butt of a gun. The white men seized Bob and hanged him, while Ike and the other Black man were relocated to another jail. The witness’s account said the white Broomes “did all that was in the power of man to do to save the lives of the prisoners.”

I don’t know whether or how these white Broomes were related to each other or to the Black Broomes, but unspoken kinship between the formerly enslaved and their white enslavers was the rule, rather than the exception, in places like Edwards. I believe that whoever wrote to the paper’s editor wanted to document all those Broome surnames across the color line, maybe to explain Ike’s survival as a magnanimous gesture, even a family favor. If the witness is to be believed, the intervention of these white Broomes is the only reason my branch of the family tree ever grew. As Auntie put it to me, “We almost didn’t make it into the world.”

Each time I pick up my research, the newspaper coverage reads differently to me. Did my uncle really unload a .38-caliber British bulldog pistol in broad daylight, as one paper had it, or do such details merit only greater skepticism? We know too much about Mississippi to trust indiscriminately the accounts in the white press. Perhaps the story offered in The Richmond Planet is the most likely: He was set upon by attackers and fired back in self-defense. But I also think about the possibility that his story unfolded more or less the way it appears in the white newspapers. Maybe my uncle Bob had had enough of being forced into second-class citizenship, and he reacted with all the rage he could muster. From the moment he refused to step off the sidewalk, he must have known that his young life could soon end—Black folk had been lynched for less. He might have sat through the church service planning his revenge for a lifetime of humiliation, calculating how quickly he could retrieve his gun.

In the Black press, Bob’s willingness to defend himself was seen as righteous. The Richmond Planet described him in heroic terms. “It is this kind of dealing with southern Bourbons that will bring about a change,” the unnamed author wrote. “We must have martyrs and we place the name of the fearless Broom [sic] on that list.” Bob’s actions were viewed as necessary self-protection in a regime of targeted violence: “May our people awaken to the necessity of protecting themselves when the law fails to protect them.” My mother has become particularly interested in reclaiming her ancestor as a martyr—someone who, in her words, took a stand. Martyrdom would mean that he put his life on the line for something greater than himself—that his death inspired others to defend themselves.

[From the September 2021 issue: His name was Emmett Till]

In 1892, four years after my uncle’s murder, Ida B. Wells published the pamphlet “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases,” in which she wrote that “the more the Afro-American yields and cringes and begs, the more he has to do so, the more he is insulted, outraged and lynched.” In that pamphlet, an oft-repeated quote of hers first appeared in print: “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home.” After the Civil War, southern states had passed laws banning Black gun ownership. For Wells, the gun wasn’t just a means of self-defense against individual acts of violence, but a collective symbol that we were taking our destiny into our own hands.

The gun never lost its place of honor in our family. My great-grandmother DeElla was known in the family as a good shot. “She always had a gun—she had a rifle at the farm,” my mother told me. “And she could use that rifle and kill a squirrel some yards away. We know that must have come from Mississippi time.” My mother’s eldest brother, also named Bob, laughed as he told me about DeElla’s security measures. “I always remember her alarm system, which was all the empty cans that she had, inside the door,” he told me. “I always thought if someone had been foolish enough to break into her house, the last thing he would have remembered in life was a bunch of clanging metal and then a bright flash about three feet in front of his face.”

The lynching more than a decade before her birth shaped DeElla and her vigilance. But as the years passed, and our direct connection to Mississippi dwindled, so did the necessity of the gun. For us, migration was a new kind of self-protection. It required us to leave behind the familiar in order to forge lives as free from the fetter of white supremacy as possible. My northbound family endeavored to protect themselves in new ways, hoping to use education, homeownership, and educational attainment as a shield.

After we studied my grandmother’s map of Mississippi, Auntie brought out another artifact: a collection of typewritten pages titled “Till Death Do Us Join.” It’s a document my grandmother composed to memorialize our family’s Mississippi history sometime after her mother died, in 1978. I imagine that she sat and poured her heart out on the typewriter she kept next to a window just outside her bedroom.

According to “Till Death Do Us Join,” my family remained in Edwards for another generation after Bob Broome’s death. Ike Broome stayed near the place where he’d almost been killed, and where his brother’s murderers walked around freely. Raising a family in a place where their lives were so plainly not worth much must have been terrifying, but this was far from a unique terror. Across the South, many Black people facing racial violence lacked the capital to escape, or faced further retribution for trying to leave the plantations where they labored. Every available option carried the risk of disaster.

[The Experiment Podcast: Ko Bragg on fighting to remember Mississippi burning]

A little more than a decade after his brother was murdered, Ike Broome had a daughter—DeElla. She grew up on a farm in Edwards near that of Charles Toms, a man who’d been born to an enslaved Black woman and a white man. As the story goes, DeElla was promised to Charles’s son Walter, after fetching the Toms family a pail of water. Charles’s white father had provided for his education—though not as generously as he did for Charles’s Harvard-educated white half brothers—and he taught math in and served as principal of a one-room schoolhouse in town.

A newspaper clipping from 1888 that

A newspaper clipping from 1888 thatmentions Bob Broome’s killing (The Boston Globe)

Charles left his teaching job around 1913, as one of his sons later recalled, to go work as a statistician for the federal government in Washington, D.C. He may have made the trek before the rest of the family because he was light enough to pass for white—and white people often assumed he was. He was demoted when his employer found out he was Black.

Still, Charles’s sons, Walter and his namesake, Charles Jr., followed him to Washington. But leaving Mississippi behind was a drawn-out process. “Edwards was still home and D.C. their place of business,” my grandmother wrote. The women of the family remained at home in Edwards. World War I sent the men even farther away, as the Toms brothers both joined segregated units, and had the relatively rare distinction, as Black soldiers, of seeing combat in Europe. When the men finally came back to the States, both wounded in action according to “Till Death Do Us Join,” DeElla made her way from Mississippi to Washington to start a life with Walter, her husband.

Grandma Victoria’s letter says that DeElla and Walter raised her and four other children, the first generation of our family born outside the Deep South, in a growing community of Edwards transplants. Her grandfather Charles Sr. anchored the family in the historic Black community of Shaw, where Duke Ellington learned rag and Charles Jr. would build a life with Florence Letcher Toms, a founding member of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.

Occasionally, aunts would come up to visit, sleeping in their car along the route because they had nowhere else to stay. The people mostly flowed in one direction: Victoria’s parents took her to Mississippi only two times. According to my mother, Victoria recalled seeing her own father, whom she regarded as the greatest man in the world, shrink as they drove farther and farther into the Jim Crow South.

Later, after receiving her undergraduate degree from Howard University and a Ph.D. from Northwestern University, Victoria joined the faculty at Tennessee State University, a historically Black institution in Nashville. During her time there, efforts to desegregate city schools began a years-long crisis marked by white-supremacist violence. Between her own experiences and the stories passed down to her from her Mississippi-born parents, Victoria knew enough about the brutality of the South to want to spare her own children from it. As a grown woman, she had a firm mantra: “Don’t ever go below the Mason-Dixon Line.” Her warning applied to the entire “hostile South,” as she called it, though she made exceptions for Maryland and D.C. And it was especially true for Mississippi.

Keeping this distance meant severing the remaining ties between my grandmother and her people, but it was a price she seemed willing to pay. My mother recalls that when she was in college, one of her professors thought that reestablishing a connection to Mississippi might be an interesting assignment for her. She wrote letters to relatives in Edwards whom she’d found while paging through my grandmother’s address book. But Victoria intercepted the responses; she relayed that the relatives were happy to hear from my mom, but that there would be no Mississippi visit. “It was almost like that curtain, that veil, was down,” Mom told me. “It just wasn’t the time.”

Yet, reading “Till Death Do Us Join,” I realized that maintaining that curtain may have hurt my grandmother more than she’d ever let on. She seemed sad that she only saw her road-tripping aunts on special occasions. “Our daily lives did not overlap,” my grandmother wrote. “Sickness or funeral became occasions for contacting the family. Death had its hold upon the living. Why could we not have reached into their daily happiness.”

I sense that she valued this closeness, and longed for more of it, for a Mississippi that would have let us all remain. But once Victoria had decided that the North was her home, she worked hard to make it so. While teaching at Tennessee State, my grandmother had met and married a fellow professor named Robert Ellis. He was a plasma physicist, and they decided to raise their four children in New Jersey, where my grandfather’s career had taken him. My grandparents instilled in their children, who instilled it in my cousins and me, that you go where you need to go for schooling, career opportunities, partnership—even if that means you’re far from home.

My grandfather was one of the preeminent physicists of his generation, joining the top-secret Cold War program to harness the power of nuclear fusion, and then running the experimental projects of its successor program, the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory, after declassification. His work has become part of our family lore as well. My mother has her own mantra: “Same moon, same stars.” It appears on all of the handwritten cards she sends to family and friends; I have it tattooed on my right arm. It signifies that no matter how far apart we are, we look up at the same night sky, and our lives are governed by the same universal constants. The laws of physics—of gravity, inertia, momentum, action, and reaction—apply to us all.

In 2011, when I was 17, Victoria died. She’d suffered from Alzheimer’s, which meant that many things she knew about Mississippi were forgotten twice: once by the world, and then in her mind. Auntie and I shared our regrets about missing the opportunity to ask our grandmothers about their lives, their stories, their perspective on Mississippi.

But Victoria’s prohibition on traveling south also passed on with her. The year Victoria died, my mother took a job in Philadelphia, Mississippi, as one of two pediatricians in the county. Two summers later, she started dating the man who became my stepfather, Obbie Riley, who’d been born there before a career in the Coast Guard took him all over the country.

Mom and I had moved quite a few times throughout my childhood, but this relocation felt different. I was surprised by how quickly Mississippi felt like home. Yet the longer we stayed, and the more I fell in love with the place, the more resentment I felt. I envied the Mississippians who’d been born and raised there, who had parents and grandparents who’d been raised there. I’d always longed to be from a place in that way.

My stepfather has that. With a rifle in his white pickup truck, he spends his Sundays making the rounds, checking in on friends and relatives. He’ll crisscross the county for hours, slurping a stew in one house, slicing pie in another, sitting porchside with generations of loved ones.

This is what we missed out on, Auntie told me in her dining room. If our family hadn’t scattered, we would better know our elders. To keep all my ancestors straight, I refer to a handwritten family tree that my grandmother left behind; I took a picture of it when I was at Auntie’s house. Every time I zoom in and scan a different branch, I’m embarrassed by how little I know. “The distance pushed people apart,” Auntie said. “I think there is some strength from knowing your people, some security.”

[Read: They called her ‘Black Jet’]

The traditional historical understanding of the Great Migration emphasizes the “pull” of economic opportunity in the North and West for Black people, especially during the industrial mobilizations of the two world wars. Certainly such pulls acted on my family, too: The lure of better jobs elsewhere, as my grandmother put it, gave Ike Broome’s son-in-law the chance to make a life for himself and his family in Washington. But this understanding fails to explain the yearning that we still have for Mississippi, and the ambivalence my grandmother had about shunning the South.

Mississippi had its own pull, even as violence of the kind visited on Bob Broome made life there grim for Black families. A 1992 study by Stewart E. Tolnay and E. M. Beck indicated that a main predictor of migration by Black people from southern counties before 1930 was the cumulative number of lynchings in those counties. The collective memory of those lynchings was a force that compounded over time. Hope and despair commingled for my family, as it did for so many others. As the physicists in my family might describe it, these forces worked in tandem to push my ancestors north, and tear them from the South.

Only after I learned the details of Bob’s death did I feel that I truly comprehended my family’s path. In returning to Mississippi, my mother and I were part of a new movement of Black Americans, one in which hundreds of thousands of people are now returning to the states where they’d once been enslaved. I think of this “Reverse Great Migration” as a continuation of the original one, a reaction, a system finally finding equilibrium. I feel like we moved home to Mississippi to even the score for the tragedy of the lynching in 1888, and for all that my family lost in our wanderings after that. We returned to the land where DeElla Broome hurried between farmhouses fetching water, where Charles Toms ran the schoolhouse.

It took well over a century for my family to excavate what happened in Edwards, buried under generations of silence. Now we possess an uncommon consolation. Even our partial, imperfect knowledge of our Mississippi history—gleaned from my grandmother’s writing and from newspaper coverage, however ambiguous it may be—is more documentation than many Black Americans have about their ancestors.

[From the November 2017 issue: The building of the National Memorial for Peace and Justice]

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, in Montgomery, Alabama, commemorates lynching victims; it is the nation’s only site dedicated specifically to reckoning with lynching as racial terror. Bob Broome is one of more than 4,000 people memorialized there. I’ve visited the memorial, and the steel marker dedicated to those who were lynched in Hinds County, Mississippi—22 reported deaths, standing in for untold others that were not documented. Although those beautiful steel slabs do more for memory than they do for repair, at least we know. With that knowledge, we move forward, with Mississippi as ours again.

This article appears in the June 2024 print edition with the headline “The History My Family Left Behind.”